Minnesota is widely known as the land of 10,000 lakes—actually, there are more than 10,000. But the state, which was the first in the nation to pass a charter school law in 1991, could also be described as the land of school choice. Beyond charters, Minnesota is also home to the nation’s first comprehensive open enrollment law, dating back to the late 1980s, which allows K-12 students to attend any public school in a district of their choice, provided there is space in the host district.

While the abundance of lakes covering the state was the result of a natural process, it would be hard to describe the rapid growth of charter schools and school choice in the North Star State as some sort of natural occurrence, driven solely by parents and teachers hungry for alternative learning environments. But Minnesota—as well as many other states and the federal government—is awakening to another approach to school improvement that is expanding, from the ground up, in a more natural way: the full-service community schools model.

In contrast to charter schools and other market-based approaches to school improvement, full-service community schools offer a holistic approach to education that is about lifting up students and the communities they live in, rather than pitting schools against one another in the interest of greater choice and competition.

Why Charters and Choice?

An overview of Minnesota’s groundbreaking charter school legislation refers to it as an attempt to fund “results-oriented, student-centered public schools.” This is an optimistic assessment of the Minnesota law that touches on the educational aspirations that the charter schools system carries, but it entirely sidesteps another important aspect of the system: the connection between charter schools and the privatization of public education.

This push to privatize the nation’s public school system has been made possible in large part by the federal government. In the 1990s, the Clinton administration readily embraced the concept of school choice by promising to close the “worst performing schools,” among other things, while seeking millions in expansion funds for the growing charter school sector. These efforts snowballed under former President George W. Bush, who funneled more than $1 billion toward supporting charter schools, often at the expense of public school districts.

Former President Barack Obama’s administration then continued along this path by pumping billions of additional taxpayer dollars into the hands of charter school operators around the country, thanks to the pro-school choice efforts by Obama’s Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

Wealthy philanthropic organizations, including the Walton Family Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, also jumped aboard the school choice train, directing millions of dollars toward the privatization of public education in the United States. The interests of both philanthropists and the federal government were most clearly united under former President Donald Trump’s leadership, when billionaire school choice advocate Betsy DeVos became the secretary of education.

Minnesota’s “first in the nation” charter school law also opened the door to charter school legislation in other states. Since the 2005-2006 school year, charter school enrollment has more than tripled; today, more than 3 million students attend such schools across the country. Only a handful of small, less-populated states, such as Nebraska, Vermont, and North and South Dakota, do not allow charter schools.

In Minnesota, there are currently 180 privately run, publicly funded charter schools, enrolling more than 60,000 students in grades K-12.

Similarly, open enrollment policies have exploded since Minnesota pioneered that option, and now nearly all states offer some sort of intra- and inter-district transfer option.

School reform models built around competition and choice have led to greater disruption in cities such as New Orleans and Chicago, where former Mayor Rahm Emanuel oversaw the shuttering of dozens of neighborhood schools amid a boom in the local charter school market.

In Minnesota, the Saint Paul Public Schools district has been left gasping for air as school choice schemes continue to wreak havoc on the district’s enrollment numbers and, subsequently, its finances.

This district is one of the largest and most diverse in the state, if not the nation, with approximately 35,000 students representing a wide array of racial and ethnic backgrounds. Two-thirds of the district’s students live in poverty, according to federal income guidelines, and almost 300 students in the district are listed as being homeless.

As a result of more school choice, in 2017, 14,000 school-age children living in the city were not enrolled in the Saint Paul Public Schools district. Instead, they either attended a charter school in or near the city or chose to open-enroll into a neighboring school district.

Just two years later, in 2019, the exodus of families had risen to more than 16,000. Today, more than one-third of all students living in Saint Paul do not attend Saint Paul Public Schools, leaving the district in a constant state of contraction.

The district’s lagging enrollment numbers can be attributed to shrinking birthrates and “a rise in school choice options,” according to a recent article by Star Tribune reporter Anthony Lonetree.

As a consequence of shrinking enrollments, district officials recently outlined a reorganization proposal that calls for the closure of eight schools by the fall of 2022 “under a consolidation plan,” in an attempt to offload expensive infrastructure costs and improve academic options for students.

Charter school options abound in and around Saint Paul, and many represent the worst effects that come with applying unregulated, market-based reforms to public education.

There’s the handful of white flight charter schools within the city limits, for example, that have long waiting lists and offer exclusive programming options, such as Great River School (a Montessori school), Nova Classical Academy, and the Twin Cities German Immersion School. On the flip side of this are racially and economically isolated Saint Paul charter schools such as Hmong College Prep Academy, where according to state data 98 percent of the students enrolled are Asian and nearly 80 percent live in poverty, according to federal income guidelines.

Hmong College Prep Academy has been in the news recently, thanks to a scandal that was dubbed a “hedge fund fiasco” by the Pioneer Press. The school is run by a husband-and-wife administrative team who invested $5 million of taxpayer money in a hedge fund, hoping it would provide a return that would help pay for the school’s expansion plans. Instead, the hedge fund investment apparently lost $4.3 million, leading to calls for the school’s superintendent, Christianna Hang, to be fired—something school officials refused to do. Hang finally submitted her resignation in late October.

In short, the market-based approach to education reform that Minnesota helped pioneer has caused a great deal of disruption, segregation and chaos. In a Hunger Games-type setting, districts and charter schools have been forced to compete for students with white, middle and upper class students and families largely coming out on top.

The end result, critics allege, is an increasingly segregated public education landscape across the state, with no widespread boost in student outcomes to show for it.

An Alternative to Choice and Competition

Thirty years after Minnesota’s charter school and open enrollment laws ushered in a mostly unregulated era of school choice, many states—including Minnesota—and federal officials may be turning their attention to the reform model offered by full-service community schools.

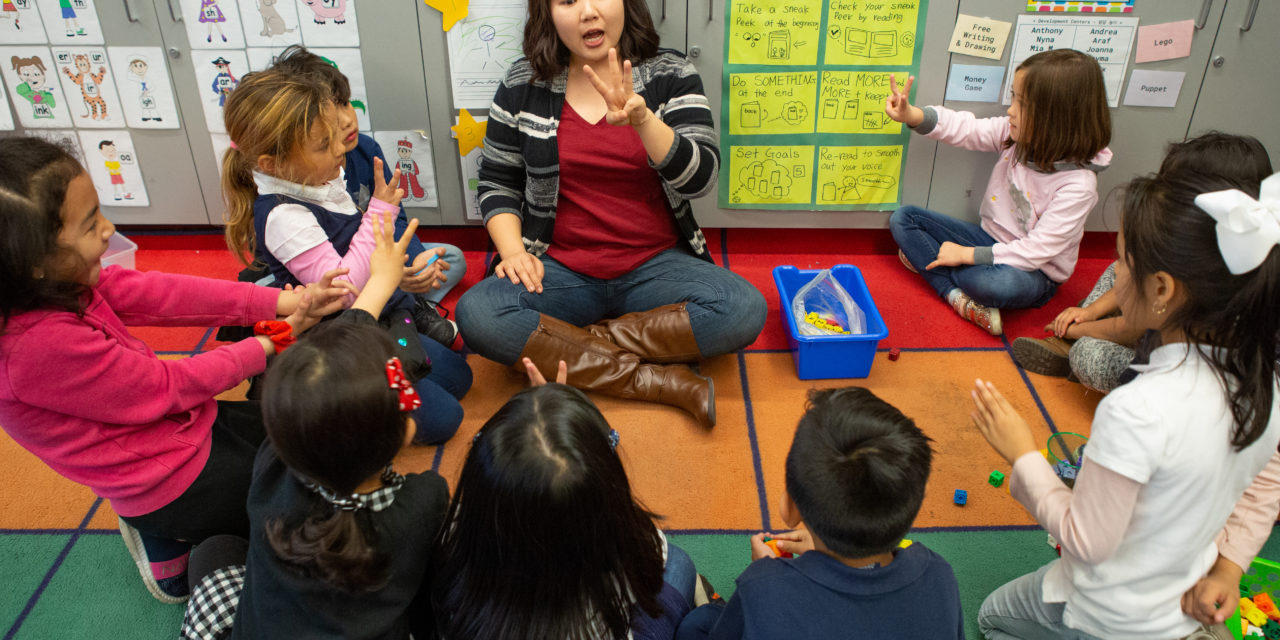

Full-service community schools offer a holistic approach to education that is about much more than students’ standardized test scores or the number of AP classes a school offers. Instead, this model seeks to reposition schools as community resource centers that also provide academic instruction to K-12, or even Pre-K-12, students.

In Minnesota, a handful of districts have adopted this model, often with impressive results.

The state’s longest running full-service community schools implementation is in Brooklyn Center, a very diverse suburb just north of Minneapolis. Since 2009, the city’s public school district has operated under the full-service model, providing such things as counseling and medical and dental services alongside the traditional academic offerings of the school system.

In recent months, Brooklyn Center’s community schools approach has been put to the test, due to both the ongoing pandemic and the unrest that erupted after George Floyd was murdered by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in 2020. In April 2021, as Chauvin’s murder trial was underway a few miles away in downtown Minneapolis, a white Brooklyn Center police officer shot and killed a young Black man named Daunte Wright during a traffic stop.

This layering of trauma upon trauma might have broken the Brooklyn Center community apart, as large protests soon took place outside the city’s police headquarters and caused disruption among residents—many of whom are recent immigrants and refugees. During this turmoil, school district staffers, already familiar with the needs of their community, were able to quickly mobilize resources on behalf of Brooklyn Center students and families thanks to the existing full-service community schools model.

It’s not just urban districts like Brooklyn Center that have benefited from this approach. In rural Deer River, Minnesota—where more than two-thirds of the district’s K-12 students live in poverty, according to federal income guidelines, and 85 Deer River students are listed as being homeless—the school district adopted the full-service model in recent years, thanks to startup grants from state and federal funding sources.

Staff in Deer River are reportedly very happy with the full-service model, which allowed them to pivot during the pandemic and provide food, transportation services and other community-specific needs. A local media outlet even noted that the community schools approach enabled school district employees to survey families during the COVID-19 shutdown and provide them with things such as fishing poles and bikes to help them get through this challenging time.

Several other districts across the United States, from Las Cruces, New Mexico, to Durham, North Carolina, have also adopted the full-service community schools approach, which is built around sharing power and uplifting communities rather than closing failing schools and shuttling students out of their neighborhoods through open-enrollment or charter school options.

Community Schools Approach Is on the Rise

Disrupting public education through the proliferation of school choice schemes, including charter schools, has long been the preferred education reform model for politicians and wealthy philanthropists in the United States, and while the charter school industry has been able to score billions in federal funding, the full-service community schools model has instead been relegated to the sidelines.

That’s starting to change.

In February 2021, a coalition of education advocacy groups, including the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers, wrote an open letter to congressional leaders asking that more federal dollars be spent on full-service community schools. Most recently, the letter notes, Congress allocated $30 million in funding for such schools nationwide, a number the coalition deemed far too low to meet the “need and demand for this strategy.”

Now, the Biden administration has proposed dramatically bumping this funding up to $443 million, based on the support this model has received from people such as the current U.S. Education Secretary, Miguel Cardona. While giving input to Congress on behalf of Biden’s proposed budget for the Department of Education, Cardona explained that full-service community schools honor the “role of schools as the centers of our communities and neighborhoods” and are designed to help students achieve academically by making sure their needs—for food, counseling, relationships, or a new pair of eyeglasses, and so on—are also being met.

If the Biden administration succeeds in directing millions more in funding toward full-service community schools, it might not be too late to save public schools, in Minnesota and across the country.

Sarah Lahm is a Minneapolis-based writer and researcher. Her work has appeared in outlets such as the Progressive and In These Times. Follow her on Twitter @sarahrlahm.

(Photo by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC 4.0.)

Recent Comments