As soon as Anna Grant’s busy workday at Forest View Elementary School in Durham, North Carolina, ended, she would head toward the next school where she was needed. “I would get off work and immediately drive to meetings, press events, whatever we had organized [for the school],” she recalls. Her second school of concern was Lakewood Elementary, where Grant now works. In 2017, Lakewood was a flashpoint of grassroots protest due to a threat by the state to take over the school.

“Roughly 200 protesters, parents and neighborhood residents” rallied at Lakewood Elementary to keep the school out of the state’s new Innovative School District (ISD), reported NC Policy Watch, a media project of the North Carolina Justice Center. The ISD was created by the state legislature to take over low-performing schools and transfer governance from the local school board to charter school management companies. Lakewood, along with Glenn Elementary in Durham and three other schools in the state, was on the shortlist of schools at risk of being transferred into the ISD.

“It’s a takeover,” NC Policy Watch quoted Bryan Proffitt, then-president of the Durham Association of Educators. “I don’t intend to allow a terrible legislative idea to ruin our neighborhood school,” Durham school board member Matt Sears told a reporter for the Herald-Sun.

Grant now calls the protests “a community effort” that united teachers with parents, community activists, and the Durham school board in an effort to stave off a transfer of school governance from the community to a private organization. The activists formed the group Defend Durham Schools to share research and talking points on state takeovers and started a Facebook page to recruit more community support.

“Our zoned school was Lakewood,” recalls Durham parent and current school board member Jovonia Lewis, “and when the state threatened to take over the school using the ISD, I joined a committee that was raising the alarm.”

The resistance was successful, as state officials dropped the Durham schools from their list of takeover targets and eventually took over only one school in Robeson County. But today Lakewood remains a much-talked-about school not for resisting the state takeover but for what happened after.

As NC Policy Watch reported in September 2019, after the successful effort to stave off a takeover, Lakewood’s performance on the state’s annual school report card assessments leaped from a grade of F to a C, and its measures of academic growth improved by 16 percentage points, with grade-level proficiency increasing by 17.6 percentage points.

“For people who believe test scores are accurate reflections of students’ academic achievement, and letter grades are valid representations of school performance, Lakewood going from an F-rated school to a C, that never happens,” Grant tells me.

“Now I know there are a lot of factors that could be contributing to that improvement,” Grant admits, “but had we been taken over by the ISD, that improvement would never have happened.”

The conversation that swirled around the takeover threat to Lakewood and how the school eventually turned its performance around is especially important now that many see the disruption that the pandemic has brought upon schools as an opportunity to “restart and reinvent” education.

“I’ve heard these calls to reimagine education as we come out of the pandemic,” says Lewis, “but what does that look like?”

Educators I spoke with in Durham answer that question by explaining a different way to think about school improvement.

Bottom-Up Rather Than Top-Down

“I was shocked that the state would consider a failed reform model that would take control of a Durham school out of our community’s hands,” Durham school board member Natalie Beyer recalls about her reaction to the threat to take over Lakewood.

The “failed” track record for state takeovers Beyer referred to is well documented in the example of an experiment in Tennessee with a similar approach called an Achievement School District. As the Tennessean reported in 2019, “Six years since it began taking over low-performing schools, new research shows Tennessee’s Achievement School District is failing.”

New York City public school math teacher Gary Rubinstein has been tracking the progress of Tennessee’s experiment over the years and reported in 2020, on his personal blog, that the state program’s promise was to take over schools in the bottom 5 percent of the lowest-performing schools, convert them to charter schools, and elevate their performance into the top 25 percent in five years. Of the 30 schools taken over, he writes, “nearly all stayed in the bottom 5 percent except a few that… [rose] into the bottom 10 percent.”

The Robeson County school taken over by North Carolina’s ISD made scant improvements since it was taken over, NC Policy Watch reported in 2019, making gains in third-grade math only and earning an F rating on its state report card.

“We’re willing to innovate locally,” Beyer says.

To act on its willingness to innovate, the Durham school board partnered with teachers and local organizations to examine school improvement models being used in communities with similar demographics.

“We studied Cincinnati a lot,” Beyer recalls. Cincinnati’s record of improving student academic measures had been reported by Greg Anrig, an author and vice president of Washington, D.C., think tank the Century Foundation, in 2013. A 2014 article in the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that the district’s model of turning schools into “community learning centers” was being hailed as a potential “national model” for urban districts.

Cincinnati schools that had taken up the community learning center model operated as “neighborhood-based ‘hub[s],’” according to a 2017 joint report by the Learning Policy Institute and the National Education Policy Center, with schools that had a special coordinator who created partnerships with local agencies and nonprofits to provide a range of academic, health, and social services to students and families.

Cincinnati schools offering these services “had better attendance and showed significant improvements on state graduation tests,” according to the joint report, based on the school district’s internal analysis.

Durham school board members also listened to local teachers rather than treating them as adversaries and worked with the Durham affiliate of the National Education Association to explore successful approaches that had been used in other urban school districts.

The consensus view that emerged from these discussions was that people wanted schools to serve as neighborhood hubs that serve the multiple needs of families. They also wanted schools, when determining their policies and practices, to be more inclusive of the diverse voices of teachers, parents, students, and community members.

Borrowing from Cincinnati’s community learning centers and what the teachers’ union called “community schools,” Durham gradually put together a school improvement approach that grew from the bottom up rather than being imposed from the top down.

‘What Excites Parents and Teachers’

“The term community schools means literally a million different things depending on where you are,” Proffitt, who is now the vice president of the state association of educators, told me in a phone call.

“Community schools is not a program,” says Grant. “[It’s] about an approach.”

These kinds of definitions can seem abstract. But an analogy from former Durham public school music educator Xavier Cason, who is now the district’s director of community schools and school transformation, helps clarify.

“Policy demands are only one part of what goes on in schools,” he told me in a phone call. “Another important part is what excites parents and teachers and gets them involved. That has nothing to do with test scores.”

When he was director of Hillside High School’s famed band in Durham, Cason knew he had to prepare his students well enough so they could put on performances at competitions that were clean enough for the judges, but exciting enough for the audience. Now, in his role in school administration, he finds he has to deliver an approach to school that passes muster with policy leaders but also delivers for parents and students.

“Back in 2016, people were saying that schools had to focus mostly on academics,” he says. “Now people have come to realize the focus had to be on educating the whole child.”

The pandemic has made this change in focus clearer, Cason elaborates, as parents and school leaders have come to realize that in order to get the academic goals they want for students, their schools need to be safe, they need to be fed, and they need access to counselors, nurses, and other support staff.

Building Functioning Democracy

But it would be a mistake to view Durham’s model for grassroots school improvement as simply a matter of adding health care and other services, often called “wraparound services.”

Formal descriptions of the community schools approach, such as the one offered by the Learning Policy Institute, frequently get into details about multiple components of the model, often called “pillars.”

But practitioners of the approach often boil it down to the fundamentals of democracy.

“Every school following the community schools approach is like a micro-experiment in building functioning democracy,” says Proffitt. This commitment to democratic governance requires schools to create structures, such as teams or committees, that are representative of the multiple voices that make up the school and that genuinely address problems people care about most.

“As you engage more people in problem-solving,” Proffitt says, “you change the culture of the community to be more inclusive of others and more committed to solving inequities.”

What does that look like? Grant explains, “[Lakewood] didn’t start off with a decision to have a mobile dental clinic. We started off with asking the community what it needed.” Eventually the school may indeed decide to start a mobile dental clinic, Grant explains, but the point is to increase engagement and participation.

In another example, Grant explains, the school started using what she calls “family engagement goal teams” to increase interaction between teachers and families. This included home visits at first, but when the pandemic hit, the work shifted to having a weekly phone bank that contacts every family, every week, via phone, text, or other means.

“When we see people participating and proposing solutions we all know need to be addressed, then we know that is the school community model happening,” she says.

The emphasis on community engagement and participation creates a sense of cohesion among the community members that make up the school, according to Grant. This greater feeling of belonging to something much bigger than yourself can lead to a heightened concern for those in the community who are struggling, Grant believes, and she points to the fact that when the school sent debit cards to every family during the pandemic, those families who believed they didn’t need the cards decided to create and organize a way to redistribute the aid to those families most in need.

“The community schools approach is an attempt to solve problems that have been in the conversation for years,” Proffitt says. But it differs drastically in how it aims to solve those problems.

“Take the issue of student suspensions,” Proffitt offers. “For years, the district has been struggling with the question, ‘Do we suspend too many students? Do we suspend too few?’ The community schools approach is a way to get beyond the question of numbers and actually engage in a conversation about how to create a school that gives kids space and grace and opportunities for correcting their behavior.”

Classroom teaching also becomes something that has to be responsive to the needs and interests of students rather than a static curriculum. When communities across the country erupted in protests against police violence targeted at Black and Brown citizens, Grant recalls, Lakewood faculty shifted the focus of their routine meetings to talk about integrating the Movement for Black Lives into their teaching and into lessons, and teachers underwent professional development on culturally responsive teaching.

“We understand we need to know what is important in our students’ lives and need to make that present in our teaching,” Grant says, “and we survey students to ask if they see themselves reflected in what we do.”

‘Building the Right Systems’

Durham educators and school board members readily admit that all the emphasis on community involvement and inclusive democracy takes time.

It also goes in the opposite direction from the decades-long trend of a school improvement model driven mostly by tests scores, and other forms of “data,” and devoted to command-and-control decisions made by central offices in local, state, and federal governments.

“Unfortunately, there are still so many pressures from standardized assessments that are not helping students,” Beyer says. “The community schools model creates some tensions for school boards because we’re still being held accountable by these state and federal measures. The state should trust local leaders and give them time and space to create what’s best for their students,” she says.

Another problem the model faces is that it doesn’t fall into the traditional media narrative of schools as places with heroic individuals—the one great teacher or the hard-charging principal—but rather as institutions with systems and problem-solving processes.

“Reporters always want those heartwarming family stories,” Grant notes, “and I could give you plenty of those, but that’s not what’s transforming our school. Building the right systems and structures is what makes this work. I know that sounds nerdy.”

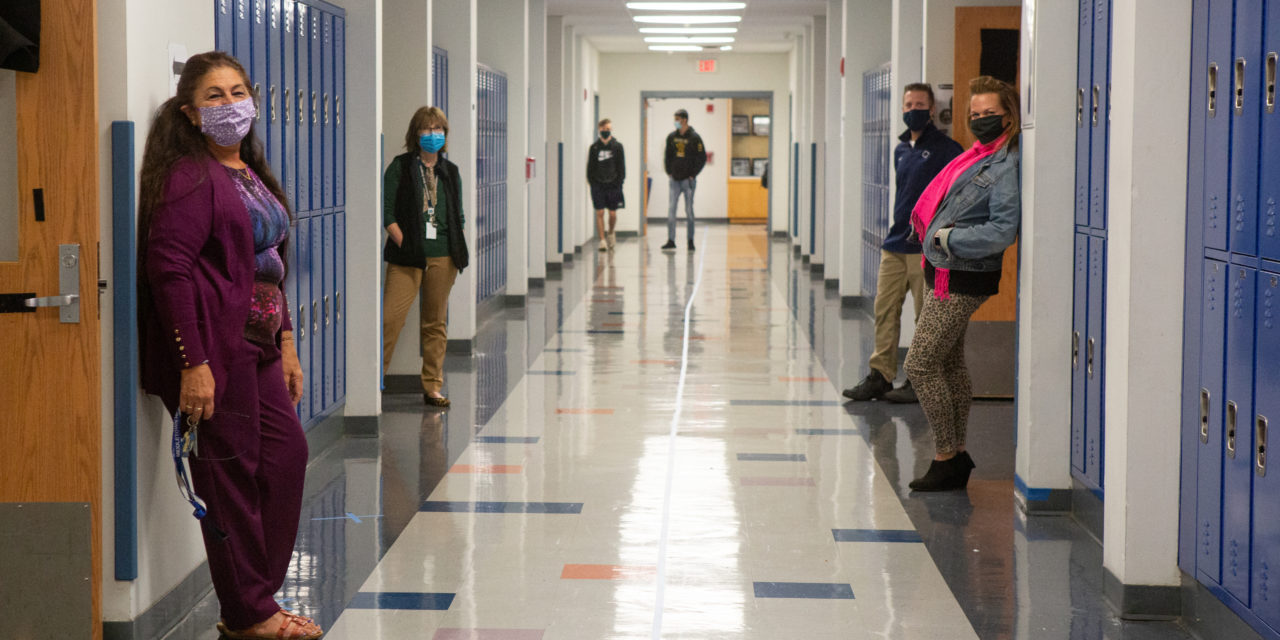

(Photo by Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.)

I support strengthening public education.

I am on your email list – I do like your latest 28JAN21 headline:

“We Need a Democratic Approach to Reimagining Schools—Asking People, Not Billionaires and Ideologues, What They Want”

I would have added to billionaires and ideologues, “and Not Just Those Majoring Only in Education”.

We should also know who is doing the “Asking” – not just politicians in our behalf, dependent on those billionaires and Ideologues, et cetera. This may turn out to be the Gordian Knot.

Almost everyone who has had contact with the school system (student, teacher, parent, or administrator) has had thoughts about What They Want. Especially as they perceive underperformance in comparison with other advanced nations – and even with some in the so-called “third world.” And also the poor preparation for life in an increasingly demanding US economy. My alma mater (MIT) often must tutor incoming US students so they can function on par with students from overseas, even in communication and math skills, but you would think it would be the other way around. What a shame!

But speaking for myself (an octogenarian with a career in engineering), I do not see some of my concerns reflected in the “Our Schools” emails. One of the problems is the one-way street on that email. I suggest you in future include a feedback mechanism such as a “comments” section to discover “What They Want”, and also to stimulate serious discussion. There is no such section now, so I used this roundabout way to offer my thoughts. Some of our ideas may be wrongly based; it would be your opportunity to learn from our input just what you need to address or criticize. Many of us are not part of the educational establishment and feel that it is sometimes more of an ivory tower affair than a democratic (small D) arena. We must become better. We cannot depend on just experts alone, or as you put it, the ideologues and billionaires, all who have let matters slip over the years. We need a truly “Democratic Approach”.

-Dave E.