In picking Connecticut Commissioner of Education Miguel Cardona to be his nominee for U.S. secretary of education, President-elect Joe Biden appears to have made a Goldilocks choice that pleases just about everyone. People who rarely agree on education policy have praised the decision, including Jeanne Allen, CEO of the Center for Education Reform, a nonprofit group that advocates for charter schools and school choice, who called Cardona “good news,” and education historian Diane Ravitch, who also called the pick “good news” because he does not seem to be aligned with advocates for charter schools and vouchers. Sara Sneed, president and CEO of the NEA Foundation, a public charity founded by educators, called Cardona an “ideal candidate,” in an email, and hailed him for “his emphasis on the need to end structural racism in education and for his push for greater educational equity and opportunity through public schools.”

But as Biden and Cardona—should he be approved, as most expect—begin to address the array of critical issues that confront the nation’s schools, there’s bound to be more of a pushback. Or maybe not?

After decades of federal legislation that emphasized mandating standardized testing and tying school and teacher evaluations to the scores; imposing financial austerity on public institutions; incentivizing various forms of privatization; and undermining teachers’ professionalism and labor rights, there is a keen appetite for a new direction for school policy.

Due to the disruption forced by the pandemic, much is being written and said about the need to “restart and reinvent” education and a newfound appreciation for schools as essential infrastructure for families and children. With an incoming Biden administration, Democratic majorities in both chambers of Congress, and the influence of incoming first lady Jill Biden, a career educator, we may be on the cusp of a historic moment when the stars align to revitalize public schools in a way that hasn’t happened in a generation.

Among the promising ideas that appear to have growing momentum behind them are proposals to fund schools more equitably, to expand community schools that take a more holistic approach to educating students, to create curriculum and pedagogy that are relevant to the science of how children learn and the engagement of their families, and to reverse the direction of accountability measures from top-down mandates to bottom-up community-based endeavors.

In her email, Sneed praised Biden’s commitment to expand the community schools model to an additional 300,000 students. She said, “My hope is that his effort will bring community schools to every part of the country, including the American South which is so often under resourced.”

Where’s the opposition to these ideas?

In her farewell address to the Education Department, before she tendered her resignation with a mere 13 days left, outgoing secretary Betsy DeVos told career staff members to “be the resistance” to an incoming Biden administration, Politico reported. In her farewell letter to Congress, she urged lawmakers to “reject Biden’s education agenda,” according to the Washington Post.

Does anyone really think there are any federal officials who will heed this advice?

During her tenure, DeVos cut more than 500 positions from her department, 13 percent of its staff, and proposed enormous funding cuts to programs. Employees accused her of “gutting” their labor agreement, reported the Washington Post, and replacing it with new rules that stripped out worker protections and disability rights, among other provisions. Employee morale “plummeted” under her management, Education Week reported, and she threatened to suspend an employee who leaked her plan to slash the department’s resources.

In Congress, DeVos was constantly besieged—from her approval, which required a tie-breaking vote by Vice President Mike Pence, a historic first, to her contentious final in-person hearing. Her proposals to dramatically shrink federal spending on education went nowhere, and her many proposals for a federal school voucher program were never taken up by Congress.

American Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten captured most people’s sentiments when DeVos resigned, saying just two words: “Good riddance.”

Instead of taking up DeVos’s calls for “resistance,” Capitol Hill seems much more likely to welcome Biden-Cardona with open arms.

An “early test” for Cardona, as Valerie Strauss of the Washington Post reports, will be deciding whether or not to let states opt out of administering federally mandated standardized tests to every student. In 2020, DeVos had let states waive the mandate, but she announced she would enforce the requirement in 2021 should she remain in office.

As Strauss reported, should Cardona decide to waive the order, he would please a broad consensus, including state and local superintendents, teachers’ unions, state and local boards of education, and federal and state lawmakers “from both sides of the political aisle.” At least one national survey has found that a sizable majority of parents want the tests canceled.

Another potentially contentious issue will be Biden’s “pledge to reopen most schools” for in-person learning within the first 100 days of his administration. Attempts to reopen schools during a pandemic have caused teachers in many school districts to rebel by writing their obituaries, staging mock funerals, resigning, calling in sick, and organizing strikes and other labor actions.

However, the operative word in Biden’s pledge to reopen is “safely.” His proposal rests on key conditions, including getting the virus under control in surrounding communities, setting health and safety guidelines recommended by experts, and providing sufficient funding to protect returning students, teachers, and support staff.

This is the complete opposite of Trump and DeVos, who simply demanded schools reopen and then did nothing to support the reopening process.

When a reporter from the Associated Press asked Weingarten to comment on Biden’s proposal to reopen schools, she replied, “Hallelujah.”

In his leadership of Connecticut schools, Cardona has taken a similarly non-ideological stance on keeping schools open in the pandemic, as Education Week’s Evie Blad explains in a video (beginning at 5:57), by “[encouraging] schools to keep their doors open” and “providing resources” and “support.” But he “never mandated” schools to deliver in-person instruction.

Congress, where Democrats have a small majority in the House and a razor-thin margin in the Senate, may be resistant to provide the necessary funding Biden wants. But as Education Week’s Andrew Ujifusa explains, Democrats are mostly united in getting a “big new relief package” passed and have a way to overcome Republican opposition using budget reconciliation.

On the issue of charter schools, vouchers, and other forms of “school choice,” which was DeVos’s signature issue, Biden has stated he does “not support federal money for for-profit charter schools,” and said they often “[siphon] off money from our public schools, which are already in enough trouble.”

Based on this measured stance, some, including Trump, have warned Biden would “abolish” charter schools and school choice, which is simply not true.

Cardona has taken a similarly evenhanded view of charters, the Connecticut Mirror reports. Under his leadership in Connecticut, existing charters were renewed while no new ones were approved. “Asked about charter schools during his confirmation hearing [for Connecticut commissioner of education],” the article notes, “Cardona said he’d rather focus his energy making sure neighborhood public schools are viable options.”

This is a refreshing change, not only from DeVos’s rhetoric for privatization, but also from previous presidential administrations, including Obama’s, that openly advocated for charter schools. It foretells that perhaps what Biden-Cardona might bring to the policy discussion over charter schools and other forms of school choice is some genuinely honest conversation rather than sloganeering about charters.

Where Biden and Cardona are most likely to encounter headwinds to their education policies are from Republicans stuck in the ongoing culture wars.

Eight days before a mob of Trump supporters, driven by the president’s tirades against losing reelection, broke into the nation’s Capitol, sent lawmakers into seclusion, and desecrated the building, Newt Gingrich, a former speaker of the House, reminded us that public education has long been a public institution in the crosshairs of right-wing ideologues. Asked by Guardian reporter David Smith, “where does the Republican party go from here?” Gingrich replied, “What you have, I think, is a Democratic party driven by a cultural belief system that they’re now trying to drive through the school system so they can brainwash the entire next generation if they can get away with it.”

Evidence of that “brainwashing” in public schools, supposedly, is the emphasis on the fully supportive inclusion of all students and protection of their civil rights that was behind many of the policy guidelines laid down by the Obama administration. DeVos rescinded many of those guidelines, but Biden has vowed to restore them.

Another source of potential discontent with the new energy that Biden and Cardona will likely bring to education policy are the holdovers of the “education reform” movement, who want to bring back in full force the top-down mandates from the Bush and Obama administrations, including charter school expansions, tying teacher evaluations to student test scores, and closing public schools based on their test scores.

For this crew, the central problem in education will always be “bad teachers,” and nothing but the most punitive accountability measures will do.

A case in point is a recent piece in New York Magazine extolling charter schools in which columnist Jonathan Chait writes that “the core dispute” in education politics is “a tiny number of bad teachers, protectively surrounded by a much larger circle of union members, surrounded in turn by an even larger number of Democrats who have only a vague understanding of the issue.”

In other words, if you don’t think cracking down on teachers and their unions is critical to improving schools, then you’re just not informed.

For decades, education policy has largely been a compromise between these two dominant factions of right-wing Republican ideologues and Democratic neoliberals, according to David Menefee-Libey, a professor of politics at Pomona College in Claremont, California. In a podcast hosted by journalist Jennifer Berkshire and education historian Jack Schneider, Menefee-Libey explains that charter schools and many other prominent features of federal education policy are the results of a “treaty” among these Republican and Democratic factions.

But as Menefee-Libey, Berkshire, and Schneider explain, in so many ways, the treaty has been broken, and after decades of attacks on public schools, we’re seeing the necessity of investing in public institutions, especially now, given the strains put on parents and communities by COVID-19.

“We are now at a point,” Menefee-Libey states, “where all of those large-scale, long-term public institutions are clearly at risk during the pandemic and the economic crash. [And] there are a lot of people [who] are discovering that maybe these institutions won’t automatically survive.”

Therein lies the golden opportunity for Biden on public education. Should he decide to go bold—not just by reopening schools with additional funding but also by proposing an ambitious investment in school infrastructure and community schools; not just by lifting burdensome accountabilities but also by actually listening to what teachers, parents, and students say they need for their schools to work; and not by trying to appease the tired, old arguments carried on by right-wing factions and reform fans in the Democratic Party—there is some likelihood he may get exactly what he wants. And that’s what our schools really need.

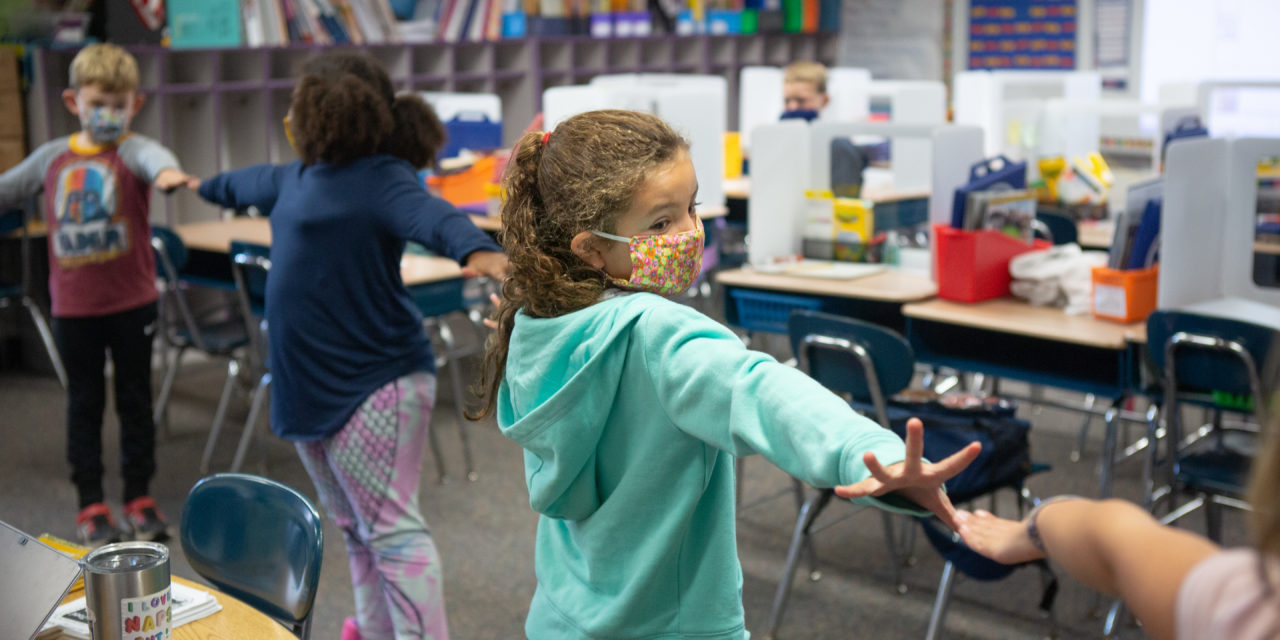

(Photo by Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.)

Recent Comments