Symbolism is powerful. It can be misused horrifically as a tool of dominance and loathing. But consider symbols countering hate, division and racism: “Black Lives Matter,” smashing the Berlin wall, even something local like renaming a York region high school after respected Somali-Canadian, journalist, Hodan Nalayeh. Symbols have the potential to galvanize people and drive change for the better- moving off well-trod paths of apathy, neglect or disdain. But it’s the length and breadth of the action beyond symbols that counts in the long run.

A special orange shirt is what Phyllis (Jack) Webstad wore to her first day at the St. Joseph Mission School in 1973. It was taken from her along with the rest of her clothes as school authorities did their best to strip her of her identity. It has become a symbol of some 150 000 Indigenous children in residential schools across Canada who were brutalized in the course of diligent efforts of governments and churches over our history to “kill the Indian in the child.” But it’s also a symbol of possibility and learning, emblazoned with the phrase “Every Child Matters.” The Orange Shirt Society (OSS) that Ms. Webstad began in 2013 helps young people and their families understand the story of residential schools, the people who survived them and, as she says, “those that never made it.”

With the uncovering of the 215 unmarked graves at the former Tk’emlups Indian Residential School in Kamloops, B.C. and 1 308 others – so far- across Canada, the orange shirt has also become the symbol of a country waking up to a fundamental truth of its history. The question, as always, is: What are we prepared to do about it?

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

The OSS’ Orange Shirt Day falls every year on September 30, a time when young residential school students would leave their families, homes and communities. The Society has really done the heavy lifting here to show the way to something broader and educational. Orange Shirt Day now coincides with the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation the new federal statutory holiday, after Bill C-5 was passed into law on June 5.

Phyllis Webstad worked hard to support the bill, but she told me that it will always be Orange Shirt Day each September 30 to honour intergenerational members of families affected by residential schools: “… in addition to the children that didn’t make it home and are still on the premises of the various sites, survivors and their families continue to die today – 2021- because of that experience and the effects of that experience.”

The new holiday is an outcome of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, created in 2008 to investigate and inform Canadians about what occurred in the residential schools that operated since before Canada was a country. Of its 94 Calls to Action, number 80 reads:

“We call upon the federal government, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, to establish, as a statutory holiday, a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation to honour Survivors, their families, and communities, and ensure that public commemoration of the history and legacy of residential schools remains a vital component of the reconciliation process.”

It’s important to note this call to action in its entirety; reconciliation calls for truth, acknowledgement and continued learning. Education is what’s at issue here. Symbolic as the day is, it is not a sop to make people feel better. It’s not the holiday – it’s the recognition of history and truth, without which reconciliation is impossible.

Acknowledging the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation

To date, only British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and the Northwest Territories are observing the national holiday. The Ontario government spouts the usual vacuous remarks: “…working in collaboration with Indigenous partners, survivors and affected families to ensure the respectful commemoration of this day within the province, similar to Remembrance Day,” in an email sent to CBC News. There’s nothing about the day on the Ministry website and educators have been directed to the TRC website for relevant information.

It’s worth noting that this government, as soon as its MPPs found their offices, cancelled

the Indigenous curriculum writing team and sent its members home with little or no warning. I spoke with Maurice Switzer, citizen of Mississaugas of Alderville First Nation. He’s a journalist – the first and probably only Indigenous publisher of a Canadian daily newspaper, serving in that capacity on the Winnipeg Free Press, the Sudbury Star and The Daily Press in Timmins. He was on that writing team and found out second hand that it was cancelled. He’s since learned that the Ministry of Education is restarting it, though, like others involved with Indigenous curriculum, doesn’t know who is on it or what it’s doing – the Ministry isn’t talking.

Colinda Clyne, Curriculum lead, First Nation, Metis and Inuit Education for the Upper Grand DSB isn’t disappointed about the day off – just the “missed opportunity” for teachers to learn about the history leading up to it. Preparing educators for Truth and Reconciliation Day was not mentioned by the Ministry in its instructions for professional development prior to the opening of school. Teachers’ knowledge of Indigenous culture and history is widely varied, she thinks, with a mass of people out there who know little to nothing about the circumstances of Indigenous people. As far as curriculum writing team is concerned, the Tories can say at least they didn’t do nothing.

That means it falls to local authorities to provide leadership. I sent messages out to 16 school boards asking about recognition of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Of those that responded, all had something planned and most boards have observed Orange Shirt Day since it began. For example, Upper Canada DSB, like most boards organizes workshops throughout the year led by Indigenous leaders, artists and story tellers. The important point here is that teaching isn’t restricted to a day or a week; it goes beyond.

Beyond Symbols

Maurice Switzer figures that the city council of his home town, North Bay, will flood the city hall in orange light on September 30. He’ll thank the city for the symbolic gesture when he speaks that day, he says, but he wants the council to go further and make a commitment for professional development on Indigenous culture and history for its 700 employees. Seven thousand of the city’s 60 000 inhabitants are from Indigenous backgrounds.

He also appreciates that governments at all levels have lowered their flags in response to uncovering the mass graves this summer. There’s not much more symbolic than a flag. North Bay flies an Ontario flag along with an Italian tricolour in honour of former Mayor Vic Fedelli, a Franco-Ontarian flag; there’s even a Canadian Air Force flag because North Bay was once a NORAD base.

Imagine he asks, the symbolic importance of flying the flag of the Anishinabek Nation high on the flagpole at North Bay’s city hall. That would be instructive.

And what about going beyond symbols to pay tribute to people who experience racism every day? “Instead of hanging our heads for a minute’s silence one day a year, what are we doing for the living First Nations people in our communities who are experiencing discrimination trying to rent apartments trying to get employment?” he asks.

Why not make more of an effort to acknowledge Indigenous people who have made contributions to Canada, people like Governor-General Mary Simon, director Alanis Obamsawan, architect Douglas Cardinal or goalie, Carey Price. Musicians, Robbie Robertson and the iconic Buffy Sainte-Marie don’t need much introduction. He adds Jody Wilson-Raybould and Murray Sinclair, the head of the TRC, to the expanding list.

Then there are role models you don’t necessarily hear about, like Dr. Bill Morrison, Professor of Biomechanics from the Métis – Chapleau Cree Fox Lake community, whose story highlights Indigenous knowledge and the relationships and respect it fosters for a scientist.

Mr. Switzer notes that when he went to university back in the 60’s, he was one of 85 Indigenous students attending post-secondary school in the whole country. Today Nipissing University alone, graduated 90 Indigenous young people in one year. Canadians need to recognize stories like these to counterbalance all the negative stereotypes we’ve been fed over the centuries.

Change led by teachers

Key to that is sustaining momentum, developing Canadians’ understanding of Indigenous peoples’ history. Maurice Switzer was delighted to see inquiries like the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), Missing and Murdered Aboriginal and Girls (MMIWG) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but how could their findings become common knowledge? There was so little media coverage on RCAP, he says, he wondered if it was deliberate. Those in charge didn’t ask “How can we make our findings and our recommendations pertinent and relevant to the average Canadian.”

Schools will fill that gap he thinks. Where provinces have followed up on their commitments to support an Indigenous curriculum, kids will learn more about the role of Indigenous peoples in Canada than their parents – certainly their grandparents: “What’s happening in classrooms is unprecedented… one of the most major societal changes in this country’s history but it’s not being led by political leaders; it’s being led by teachers.”

“It’s the conversation that matters,” says Phyllis Webstad. Teachers need to start somewhere; listen to the stories of people while being mindful of their healing. They can seek advice from Indigenous groups across the country with access to speakers and authors. Ms. Webstad wrote Phyllis’ Orange Shirt about her experiences, as well as “Orange Shirt Day” telling the story behind the day.

Alberta teacher Robin Drinkwater, developed a curriculum for the Orange Shirt Society for kids from Kindergarten to grade 6 that builds understanding of how “every child matters” in families, schools and communities, gradually adds elements of Indigenous culture, understanding of loss and, as students get older, what it meant to face the foreign world of residential schools, while no longer fitting in back home. Books like Fatty Legs and A Stranger at Home: A True Story by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton are a couple of examples of so many important stories that illuminate this history.

There’s one important note to add here: consider the audience. Colinda Clyne cautions while it is important it is to deal with the facts of history, educators need to be aware this day can be triggering to some young people. So, consider what happens if you have Indigenous kids in your class as she says: “How do you take care of those students?” Their parents need to be aware of events in the class, so they can keep them home, if needs be.

Keep up the work – but have a plan.

Important as symbolism is, getting beyond it is an excruciating challenge to those who care to see change. After generations, Indigenous people still can’t rely on access to clean water and electricity in their communities. Housing is a disgrace and they are grossly overrepresented in prisons throughout the country. Suicide amongst adults and youth is a national tragedy. Yet, the recently elected Liberal government continues to fight an order from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) to pay $40 000 to Indigenous children taken from their on-reserve homes. It’s stunning.

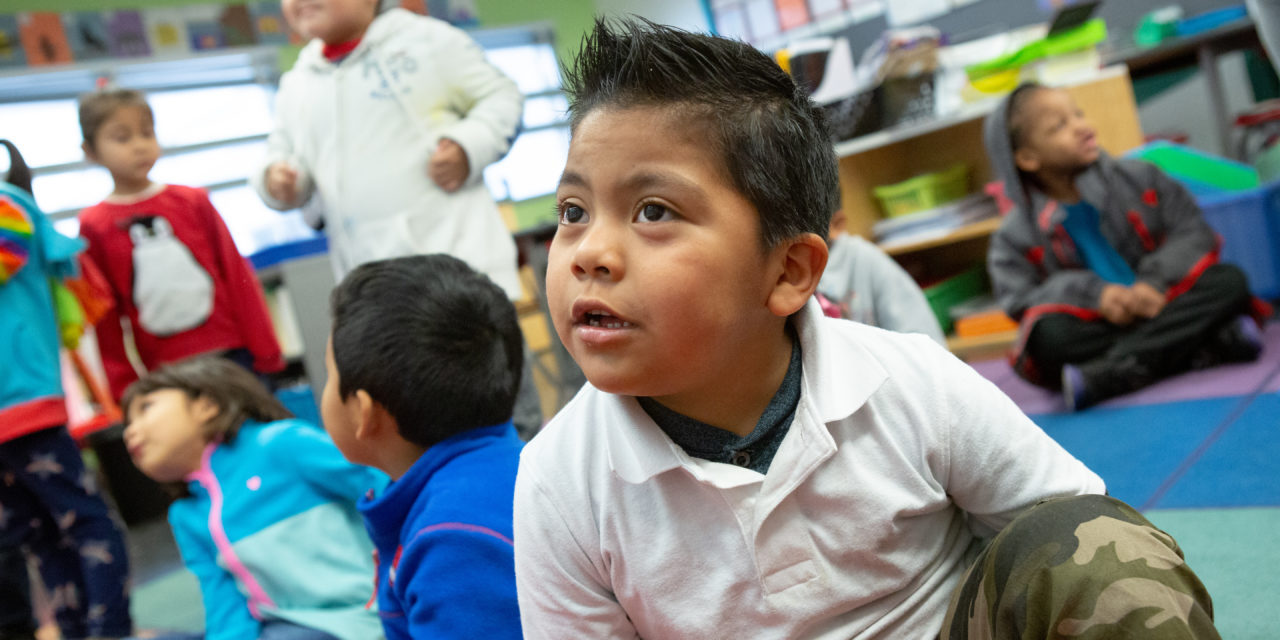

The real hope of reconciliation comes from kids, open-minded by age and nature who are capable of absorbing new ideas with little effort. They will move the dial of history if they are taught by good teachers – and take the rest of us with them. Truth and Reconciliation Day is all about education.

Originally published by School Magazine (Education Action Toronto).

(Photo by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages, CC BY-NC 4.0.)

Recent Comments